Welcome to email number two from Laughing Stock. This week, Connah Roberts (@connahr) sees whether there is anything to read from Arctic Monkeys referencing quantitative easing in their recent album Tranquillity Base Hotel & Casino.

In the most recent Arctic Monkeys' album the lead singer Alex Turner makes a reference to quantitative easing (QE). Released in 2018, the album Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino was a commercial and critical success, if we are to count what is left of the mainstream music press as critical. Radio 1’s Annie Mac described the record heading in an exciting new direction, ‘partly because it had been written on piano and not a guitar’. Either way, it seems quite interesting to have arrived at the point where a very popular, stadium sellout band is referencing central banks buying bonds, essentially creating money, in order to pump the economy and stimulate growth (QE). Why are Arctic Monkeys, and specifically Alex Turner, who writes all the lyrics, making this reference?

Turner formed this album alone and, after sharing it with the rest of the band, it was discussed whether it should be a solo album. Evidently it was decided against. Arctic Monkeys sound derives from its nostalgia. Of course it has, in some ways, been essential to some of the lyrical foundations but it is simply a rehash of a bygone era. A coming together of all that has been before. From the beginnings of indie in the 70s and 80s through Britpop to the early 00s with bands like The Strokes. A typical band quartet, lower middle-class and working-class lads with guitars and a drummer. This formation, and history, keeps Turner in check, keeps his songs on the right side of popular, and may well be the safety net for him not to release solely.

Arctic Monkeys were difficult to escape if you were a teenager in a Northern city or town in the mid 00s. The song Riot Van from their first album in 2006, was a mirror for groups of 13 and 14 year olds who would be roaming the streets playing knock and run, drinking the odd beer, winding police up with the familiar call of “go and catch some real crime.” At that age, it gave some value to our lives knowing others were up to the same. You would then relate to wearing converse for the first time, jumping cabs once you started going to gigs, narky bouncers, ringtones sent via bluetooth, house parties when parents were away, all of which referenced in Turner’s songs. No doubt this experience has been written about before but you always fall for the narratives that you first come into contact with.

Age moves on, faster internet arrives in your bedroom, and you have the freedom to visit different cities. If you were into music you would eventually end up subscribing to Boomkat’s newsletter, creating lists on Discogs, and listening to Rinse, while browsing the many other wonderful blogs and sources which I won’t go into detail about here. Without that readiness of endless amounts of information bringing with it the ability to truly hear genuinely new sounds for the first time, Arctic Monkeys were it. You didn’t really have much of a choice. Therefore, I would always keep tabs on what Turner was writing about as some form of homesickness for past times. The lyrics have fairly always been the same since the first album in 2006 until 2018: drink, drugs, relationships. However, when first seeing the lyrics on this latest album, it was a bit of a surprise to see its themes: mass technology, surveillance, class and, of course, quantitative easing. It seemed to resonate more thematically with Sam Kidel’s effort on Death of Rave or Hanne Lippard’s recent LP. Both of which are attuned to the absurdity of this world today, depicting the reality of life under neoliberalism and the tediousness of work.

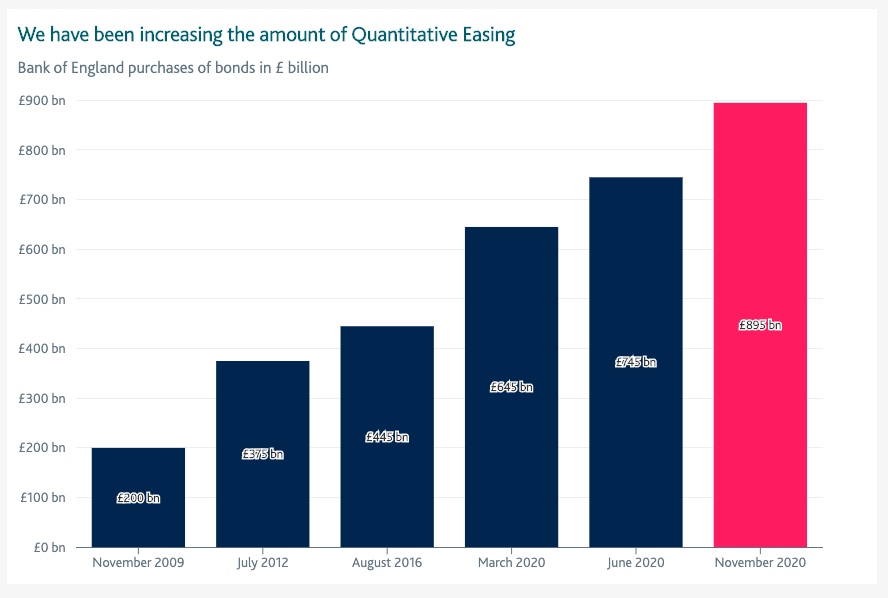

QE has now become an economic dogma of many capitalist states. It is seen by some as a form of post-Keynesianism action trying to keep the economy on track and inflation steady. We need inflation otherwise, as Grace Blakeley points out, why buy goods today if they will be cheaper tomorrow (deflation). Deflation occurs when consumer confidence is low and people stop spending. QE as a theory has been talked about since the 1980s. It was first implemented in Japan, four years after the Asian stock market crash in 1997. This inspired Ben Bernanke, once head of the US Federal Reserve, to lay out the policy for America in 2004. In 2009, after the financial crash, Britain followed suit. To clarify, QE involves central banks buying bonds (loans), and assets, either corporate or government, in order to inject cash into the financial sector and, therefore, the economy. The Bank of England, for example, electronically creates money, literally numbers on the screen, gives it away by buying assets in the hope it trickles down through lending, due to low interest rates and more money being available, to businesses and households. The expectation is to boost consumer confidence as asset prices rise, such as the value of homes, and lending becomes cheaper for businesses and households wanting to make purchases. This is QE, which has had an impact on everyone’s life. This is one of the reasons why you might be lucky enough to have parents who are sitting on cash cows, or it’s the reason why you’re struggling to pull together a deposit as house prices keep on rising. Even as far back as 2012, the Bank of England knew QE was benefiting the top 10% of the country more than it was the rest, as they were the ones who owned assets. A simple understanding of how it hasn’t worked for those who need it is explained by Mark Blyth. As he states, QE is like turning the kettle on then putting a hose pipe through your letterbox and switching it on full blast. Eventually some of the water will go in the kettle but the home will be flooded. Below shows how much money has been created by the Bank of England since 2009.

So why is Turner referencing QE now? The lyric comes in the song Science Fiction, with its syntax linked to a line in the opening ‘rise of the machines.’ The song continues with lines where Turner is aware of what he can and cannot say while stating what it is he wants to stay: ‘I wanna make a simple point about peace and love / But in a sexy way where it's not obvious / Highlight dangers and send out hidden messages / The way some science fiction does’. In a way this metaphysicality has always been there through their songs but now has moved to the wider world, such as monetary policy. Trawling through message boards when researching this, it turns out he mentions wanting to write about QE in 2015 but instead sticks to writing about “women.” Confirming some sort of anxiety about then making political comments on the wider world. (See from 7 mins 45 seconds in this video.) It is still rare to hear regional accents talking about economic policies or sensible ideas in the main and it not be labelled ‘broadband communism’. By all means you hear them on Tribune podcasts or Novara streams but they ain’t popular. It was a shock to hear a regional accent on In Our Time recently, the episode was on Karl Marx.

There are two early songs from Arctic Monkeys' back catalogue which question the game of the music industry. In the 2006 songs ‘Who The Fuck Are Arctic Monkeys?’ and ‘Perhaps Vampires Is A Bit Strong But..’, Turner writes with uneasiness, claiming not wanting to take part in recouping ‘what we spending’. A resistance to some clever marketing campaign or another, which many bands at the time were doing and continue to do today. One only has to look at Working Men’s Club recently redecorating Manchester’s Yes club for the release of their first album. But then, Turner has turned into a walking contradiction. Writing from the inside looking in. For this latest album the band opened pop-up shops in various locations featuring an art exhibition and Arctic Monkeys branded goods. The one in Sheffield filled the space that was once occupied by a Google Digital Garage. The modern day capitalist library. Where you learn skills to thrive and build confidence. (Irony here being even QE didn’t help Google survive on the high street.) They too were part of Danny Boyle’s austerity nostalgic London 2012 opening ceremony, they all avoided tax and were caught in 2014, and now Turner is a pastiche of the character depicted in Fake Tales of San Francisco.

Nevertheless, there is definitely an oddness for a number 1 selling album to now reference QE. A helplessness delivered to a global mass audience. A disillusionment of our connected world. How much do we need to talk about the elephant in the room, neoliberalism, for it to change? Maybe it is a sign of the times post the 2008 crash: quantitative easing, austerity, Facebook, Brexit, the arrival of Trump. Those losing out, those benefiting. Those who own assets, those who don’t. Those gammons, those vegans. Yes, no. What this album seems to prove is what the left can never understand. Something that has happened throughout history in other works of science fiction and political movements. We can critique as much as we like, we can beg, we can argue, we can be kind, we can be angry, but nothing looks set to change. Finance is power and power is finance. A big organising force can mobilise behind a socialist leader offering the world and it still be met with suspicion. Alex Turner can reference QE as the Bank of England uses it to create £2,285,000,000,000 (trillion) in 2020 alone. While in the real economy, and the real world, those on Universal Credit have to fight for a £20 increase and kids on free school meals need a footballer to get more than half a pepper, a quarter of an onion and food in money bags. Here’s to this century’s roaring 20s, eh.

Each week we will share some tracks that the contributers to Laughing Stock currently have on heavy rotation. You can follow the rolling playlist on Apple or Spotify.